The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek: An Interview with Kim Michele Richardson

It’s not unusual for Bas Bleu to receive multiple Reader Reviews or customer recommendations for a single title…but usually these roll in over the course of several years. Last fall, our editors noticed a decidedly steady influx of Reader Reviews for Kim Michele Richardson’s novel The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek. One reader even sent us a copy of the book! We took a closer look and were immediately enchanted by the moving fictional tale of Cussy Mary Carter, a young woman born with unusual blue-tinted skin who defies poverty and prejudice to serve her community as a pack horse librarian in rural 1930s Kentucky. Recently, we had the opportunity to chat with the author about the incredible real-life people who inspired her characters, the importance of recognizing overlooked women in history, and the librarian who made a difference in her life.

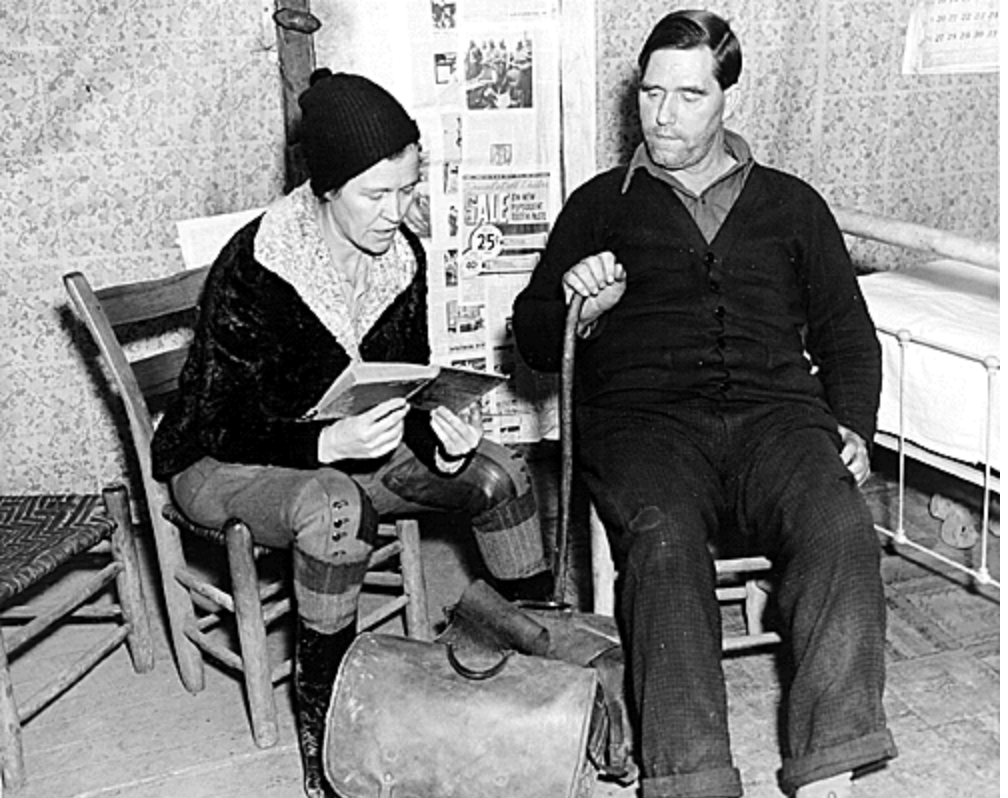

Bas Bleu: Before your novel, we knew little about the Pack Horse Library project, but it was enough to leave us impressed by those indomitable book women. Was the project unique to Appalachian Kentucky? How was it conceived? What was the most surprising thing you learned about it?

Kim Michele Richardson: It was actually in 1913 when the Kentucky Federation of Women’s Clubs convinced a local coal baron, John C. Mayo, to subsidize a mounted library service to reach people in poor and remote areas. But a year later the program expired when Mayo died. It would be almost twenty years until the service was revived under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA), as an effort to put women to work by bringing books and reading material to the poorest and most isolated areas in eastern Kentucky.

The initiative alone was a fascinating, unknown part of history, but having it mostly women-driven made it more unique. It showed fierce, courageous women in an unforgiving landscape, accomplishing what many never could, and battling everything from inclement weather, mistrust, treacherous landscapes, and extreme poverty, and doing it all in Kentucky’s most violent era—the bloody coal mine wars.

Also, women who defy the odds, achieve great measures, both in the past and present, should be recognized as more than a blip in history, and should be lifted up and shown for the true heroes they are.

I was surprised that I had been unable to find these women in novels. For eighty years these Kentucky pack horse librarians were ignored with the exception of several amazing children’s books—the women’s historic legacy but a small footnote in history. To be able to share my novel—about a little-known American portrait of the indomitable spirit of these literacy pioneers that highlights the remarkable journey of my brave Kentucky sisters who worked for the pack horse librarian initiative project—has been a privilege and one of my greatest honors.

BB: One of our editors is married to a Kentuckian, and her husband and in-laws were surprised to learn about the blue-skinned people of their home state. How did these folks fly under the radar for so long? What finally brought them to the attention of the wider world?

KMR: It was in the 1960s when Madison Cawein, a Kentucky hematologist, heard about the blue-skinned [Fugate family] and set out to find them. In the 1940s, a doctor in Ireland made similar discoveries among his people. Today, the blue-skinned people of Kentucky are taught in biology classes in schools. I learned of the Fugates long ago and became endeared with them after I found out how unfairly they were treated. I wanted to give them a voice they’d long been denied due to ignorance, stereotyping, and misunderstanding of their medical condition.

BB: You probably could have written two complete novels, one about the Pack Horse Library project and one about the blue-skinned people of Kentucky. What did you hope to accomplish by combining the two subjects? What did they bring out in each other that might not have been evident if you’d treated them separately, in separate novels?

KMR: I hoped to embrace their strengths and uniqueness in story. There was such rich, magnificent history in the two, I was surprised I hadn’t seen them in a novel, that neither had been given a footprint in literary history. I knew it was time for the wider world to experience them in a novel, to learn about, to see, the indomitable Kentucky Pack Horse librarians and the precious blue-skinned mountain folk.

BB: Your novel is historical fiction, but it’s still fiction. As a novelist, how do you decide when (or if) to take artistic license with historical fact? How do you honor the lives of real people without feeling like you’re appropriating their experiences for the sake of plot or character development?

KMR: As a Kentuckian, I have a great love for the land and my people. These are my people, this is my place. In a way, my whole life was preparation. Of course, much of this is out of my direct experience; I wasn’t even born when the pack horse librarians were riding. Most people writing now were not. Respect for their lives requires extensive research. I spent five years and thousands of hours doing just that. My husband contracted Lyme disease and I was seriously injured because we left home and moved to Appalachia for a year so I could further authenticate the work.

And as a survivor of abuse, I can relate to marginalized people and have much empathy for Cussy Mary and her family and the people of eastern Kentucky—anyone who has faced or faces prejudices and hardship. It’s not hard to feel pain deeply, particularly if you’ve gone through hardships in your own life.

For years, I worried about my native Kentuckians, fretted about giving this small group the true and honest voice they never had. I wanted to lift them up, and educate folks about these isolated people who had been shunned and shamed because of an extremely rare hereditary gene disorder.

A year ago I awoke to a surprise email from Douglas Fugate, a former librarian and a descendant of the blue-skinned people of Kentucky. Mr. Fugate had just finished reading an advance copy of The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek, and he gave the work glowing praise and his highest rating. It was the strongest validation I could ever receive for my most important work.

Miss Richardson’s writing is superb. Her landscape descriptions, the attitudes of both the mountain folk and those who avoid them are on the mark. She is extremely accurate in her descriptions of racism and prejudice depicted in the mountain communities and large and small towns and cities in the country. There are moments when you will shed a tear. You will feel the pride of accomplishment as the children feast on the written word. You will feel the embarrassment of being an outcast, and rejoice in the human compassion expressed through various characters. These events will leave the characters, the events and the feelings with you long after you have finished the book. I have relations that come from Troublesome Creek. I have discovered that I, too, have the “blue streak” in my blood. I was delighted with the whole work and sad when I came to the last page. This is a wonderful story and well worth your time. FIVE Stars.—Douglas J. Fugate 1SG, USA Retired

During a speaking event, I received additional praise when I had the honor of meeting more descendants who told me how much the The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek meant to them and how grateful they were for the work. Another descendant, a young Kentucky librarian, was moved to tears by the heartfelt beauty and honesty of the novel, and she called it a “wonderful must read.”

BB: Cussy’s story is heartwarming in many ways, but you don’t spare readers her grim realities—poverty, hunger, isolation, bigotry, grief, even violence. As a writer, how would you respond to a reader who says, “I read novels to escape from reality, I don’t want to read about unlikeable characters or sad things.”?

KMR: Maybe they aren’t my reader? Not everyone in the world has to read my book. I wonder if a lot of folks like your imaginary reader exist? I’m sure there are a few, but I think most readers have a broader spectrum than that. Maybe today they need a twisty read like Joshilyn Jackson’s smart, original thriller Never Have I Ever, or a meaningful and heartfelt tale like The Favorite Daughter by Patti Callahan Henry, or tomorrow they might want a light, sweet love story or touching memoir.

I love exploring my birthplace in my writings; the beautiful, brutal, and mysterious Kentucky land and its people—the historical social injustices and the unusual and cherished traditions, myths and legends of my state. More than anything, I write human stories set in a unique landscape. Knowing one small piece of this world—the earth, the sky, the plants, the people, and the very air of it—helps us understand the sufferings and joys of others ourselves.

So when the day comes when the reader wants to read about an authentic and realistic (and, yes, heartwarming too) slice of history about a group of extraordinary women—well, Cussy Mary will be waiting.

BB: We suspect all readers have a soft spot for librarians. But was there a particular librarian or library that made a major impact on your life?

KMR: I spent the first decade of my life in a rural Kentucky orphanage and then on to foster care and beyond, finding myself homeless at age fourteen. As a foster child, I remember going to my first library one lonely summer and checking out a book. The librarian sized me up and then quietly said, “Only one? You look smarter than a one-book read, and I bet we can find you more than just one.” She reached under her counter, snapped open a folded, brown paper sack, handed it to me, and then marched me over to shelves filled with glorious books. I was shocked that I could even get more than one book, much less a bag full of precious books, and I was moved by her compassion, kindness, and wisdom. Librarians are lifelines for so many, giving us powerful resources to help us become empowered.

BB: Book Woman is your fourth novel, all of which are set in Kentucky and/or Appalachia. What misconceptions do you think people have about the region and its residents? What truths do you hope your readers glean from your books?

KMR: The people of eastern Kentucky have long endured many hardships and sufferings. Even in today’s news we witness the Kentucky coal miners working 16-hour shifts down in the mines, and the appalling theft of paychecks by rich coal companies—the wealthy who come in to stomp down on the poor’s back to make themselves stand taller.

When writing this novel, I knew it wouldn’t change the world, but if I’d planted seeds of kindness, courage, and empathy in the tumultuous and charged world we now live in, I think that’s all I could hope for.

BB: Which book(s) from your childhood helped to shape the person you are today?

KMR: On rare occasions, a tattered children’s book would make its way into our dormitories at the orphanage. I remember reading a very dog-eared Heidi by Johanna Spyri. I marveled over the red cloth hardcover and decorative end pages that featured joyful children racing along the Alm, sledding down snow-capped mountains. It was so beautifully illustrated, and the words seemed to speak to me. Immediately, I realized that books were prized, magical treasures—that I could maybe one day have a grand life like those in the books, beyond the cold, silent, ugly institutional walls.

E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web was a masterpiece that tapped into my love for nature and animals. And every time I read it, I learned something new. It has the wonderful Hitchcockian first line: “Where is papa going with that axe?” and is infused with magical verses of dewy spider webs, “Some Pig” miracles and unconditional friendship. Some Book!

BB: Which books are you quick to recommend to other readers?

KMR: Currently, I’m excited for a lot of books coming out in 2020 that I’ve had the opportunity to read in advance. Before Familiar Woods by Ian Pisarcik is a haunting debut with unforgettable characters set in a poor and desolate landscape, along with Ashley Blooms’s Every Bone A Prayer, a powerful, heart wrenching and healing tale set in Appalachia. Oona Out of Order by Margarita Montimore will mesmerize and blow your mind.

For the nonfiction reader, the paperback release of The Ghosts of Eden Park by Karen Abbott arrives in the spring. It’s a stranger than fiction tale, the nonfiction answer to The Great Gatsby, and the best nonfiction tale you’ve read in years.

BB: Who are your favorite authors?

KMR: There are so many talented writers out there to pick from, it makes the choice difficult. But Harriette Simpson Arnow, John Fox Jr., Gwyn Hyman Rubio, and Walter Tevis are some of my longtime favorite Kentucky novelists who wrote unforgettable masterpieces. Each one brings the pages to life with rich, evocative landscapes, beautifully told stories, and highly skilled prose.

BB: What future projects can our readers look forward to seeing from you?

KMR: I’m exploring several, so it’s too soon to reveal.

BB: Thank you, Kim Michele Richardson, for sharing such incredible history and perspective with us!

Novelist Kim Michele Richardson (photo credit: Leigh Photography)